Peering Beneath the Surface

The Moon’s glow has inspired countless stories, but its inner workings remain a mystery that science is steadily unraveling. Researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have harnessed gravity mapping to explore the Moon and the asteroid Vesta, revealing details about their interiors that reshape our understanding of these distant worlds.

Using data from spacecraft that orbited these bodies years ago, scientists have crafted precise gravity models. These models capture subtle changes in gravitational fields, offering clues about what lies deep inside without ever landing. The findings, shared in top journals, illuminate the past and guide future exploration.

This work connects to a larger quest to understand how planets and asteroids formed. By studying the Moon and Vesta, researchers refine tools that could one day probe the interiors of other celestial bodies, from icy moons to rocky planets far beyond our solar system.

The Moon’s Two Faces

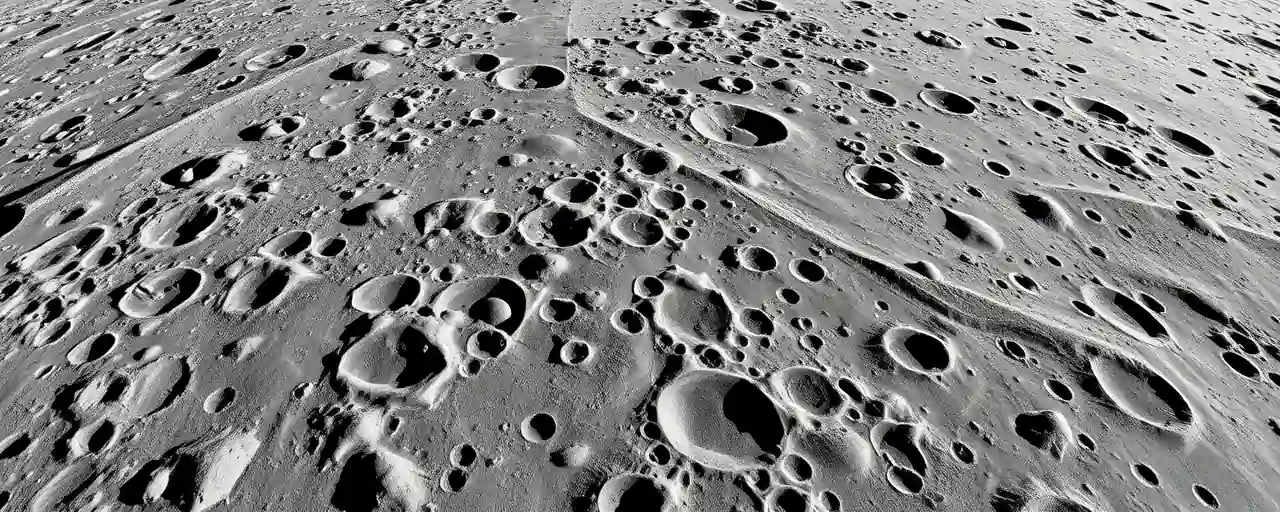

Anyone with a telescope can see the Moon’s near side, marked by dark, flat plains called mare. The far side, hidden from Earth, is rougher, with craters dominating the landscape. A study published on May 14, 2025, in Nature used data from NASA’s GRAIL mission to investigate why these two sides differ so starkly.

The research revealed that the near side bends more under Earth’s tidal pull, hinting at a warmer mantle rich in heat-producing radioactive elements. This warmth likely fueled volcanic eruptions 2 to 3 billion years ago, forming the mare. The far side, less flexible, lacks such activity, explaining its rugged terrain.

This work also produced a highly detailed lunar gravity map, a vital tool for future missions. Astronauts and rovers could use it to navigate with greater precision, supporting plans for lunar bases and scientific outposts.

Vesta’s Unexpected Uniformity

Vesta, a massive asteroid orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, holds secrets about the solar system’s early history. A study published on April 23, 2025, in Nature Astronomy analyzed data from NASA’s Dawn mission, expecting to find layered interiors and a dense core. Instead, it found Vesta’s mass is spread evenly, with only a small core, if any.

Scientists measured Vesta’s spin and wobble to calculate its moment of inertia, which shows how mass is distributed. The even distribution suggests Vesta may have formed from debris after a collision or never fully separated into distinct layers, unlike planets like Earth with heavy iron cores.

These results challenge existing theories about asteroid formation and highlight the variety of structures in our solar system. They also show how gravity measurements can reveal surprises about worlds too distant to visit directly.

A Revolution in Planetary Study

The methods behind these discoveries are transforming how we study planets. Cutting-edge tools, like the THeBOOGIe gravity inversion scheme, let scientists map density variations with remarkable accuracy. Supercomputers at NASA and ESA’s Space HPC, launched in March 2025, process massive datasets, turning raw numbers into vivid pictures of planetary interiors.

These techniques have already shed light on other bodies, such as Jupiter’s moon Io and the dwarf planet Ceres, each with unique internal features. The ability to analyze planets remotely expands the reach of future missions, especially to places where landing is challenging or impossible.

Practical benefits abound. Accurate gravity maps could guide lunar exploration under NASA’s Artemis program, while understanding asteroid interiors informs strategies to redirect hazardous objects, a key concern for those focused on protecting Earth.

Balancing Science and Resources

Funding for planetary science sparks lively debate. Some policymakers push for leaner budgets, prioritizing projects with clear national security benefits and proposing cuts to NASA’s science programs. Others argue for strong investment in research, pointing to its role in driving innovation and fostering global partnerships, as reflected in the Senate’s 2025 budget boosts for planetary science.

Meanwhile, private companies are changing the game. Venture capital is pouring into lunar landers and space startups, with the space economy projected to hit $2 trillion by 2040. Programs like NASA’s Artemis blend public and private efforts, speeding up exploration while prompting discussions about who benefits from new discoveries.

Charting the Path Ahead

Gravity mapping is opening new windows into the solar system. As tools grow more sophisticated, scientists plan to study far-off moons and asteroids, each offering fresh pieces of the cosmic puzzle. Upcoming missions to return samples from the Moon and Mars will add even more data, building on recent studies of asteroids like Ryugu and Bennu.

These findings do more than advance science; they connect us to the broader universe. Learning about the Moon’s volcanic youth or Vesta’s simple structure helps us trace the origins of our solar system, a story billions of years in the making. Every discovery adds a chapter to that tale.

As we prepare to revisit the Moon and venture farther, gravity mapping will light the way. It offers both practical solutions for exploration and deeper truths about the worlds around us, guiding humanity’s next steps into the cosmos.